What is Champix?

Champix (Varenicline), its type of medication designed to aid people in giving up the habit of smoking. This treatment, know as a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, works by stimulating the same receptors of the brain that smoking nicotine does which helps reduce cravings. With a success rate of around 44%, this treatment is far more effective than its only competitor, Zyban. Since its release in January 2007, Champix has fast become one of the more popular options for patients looking to end their addiction to nicotine.

How Does It Work?

Champix works by stimulating the same receptors in the brain as nicotine. This makes it possible for Champix to remove all the cravings and withdrawal symptoms which would normally be experienced if you were to stop smoking. As well as this action, Champix also works to block the receptors from any nicotine inhaled, which means that the rewarding affects that nicotine would usually have on the body are no longer effective.

What's the difference between Champix and Zyban?

Zyban as it is also known, was originally developed and approved as an antidepressant and was only later discovered to have some degree of benefit with smoking cessation. The way in which this treatment works is not presently understood by the medical community, but it is known that Zyban affects the neurotransmitters (chemicals stored in nerve cells) noradrenaline and dopamine by increasing the amount of these in the brain which is believed to help reduce cravings.

The success rate of Zyban is approximately 29%, which in comparison to that of Champix which has a success rate 44%, is considerably less, rendering this treatment far less effective in helping people stop smoking. Further, the results of several comparative studies have found Champix to be far more effective even in fewer doses.

How is this champix treatment taken?

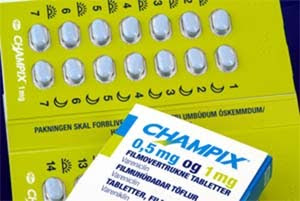

Champix comes in tablet form and is taken for a period of 12 weeks. Your course of champix treatment will comprise of a starter pack which contains 11 x 0.5mg white tablets and 14 x 1mg light blue tablets. These different doses are used as described below:

• From day 1 to 3 – take one 0.5mg dose of Champix daily

• From day 4 to 7, take one 0.5mg dose of Champix twice daily, once in the morning and once in the evening, at approximately the same time each day

• From day 8 to 14, take one 1mg dose of Champix twice daily, once in the morning and once in the evening, at approximately the same time each day

• From day 15 onwards until you have completed your course of treatment, you should take one 1mg dose of Champix twice daily, once in the morning and once in the evening, at approximately the same time each day.

If you experience unpleasant side effects once you have started taking the 1mg dosage of Champix, it is possible to revert back to the 0.5mg dosage, which will be taken twice daily for the remainder of the treatment. You will need to inform our customer service department who will take information from you regarding these champix side effects and seek the advice of our doctor.

What are the side effects of Champix?

As with all prescription medications, there are several possible side effects attributed to Champix. The more common side effects, which you will more than likely not experience at all, include nausea, insomnia, abnormal dreams and headache. These champix side effects are usually mild with fewer than 3% of patients ceasing treatment as a result.